Low-level Laser Therapy for Fat Layer Reduction a Comprehensive Review

Abstract

Obesity and overweight is a global wellness crisis and novel methods of treatment are needed to address it. Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is a currently available non-invasive procedure for lysing excess fat, but there is a lack of consensus exists on LLLT frequency and limited research from studies of LLLT. The purpose of this airplane pilot study is to compare the effect of three of the most mutual LLLT frequencies on weight, waist circumference, body fat percentage, and quality of life. Sixty overweight (body mass index (BMI) 25–29.nine kg/m2) adult participants were randomized to 12 LLLT treatments: (1) 3 times weekly for iv weeks, (2) twice weekly for vi weeks, or (3) in one case weekly for 12 weeks. All participants attended an in-person visit at baseline and at weeks iv, 6, 12, and 26. Participants were recruited September 30, 2016 through to August 27, 2017. The majority of the 60 participants were female (xc%) with an average age of 43.seven years (± 9.2 years). Most participants (98%) completed x or more of the 12 LLLT treatments. When comparison across treatment groups, the greatest reductions from baseline were observed in those assigned to twice weekly for half-dozen weeks in weight (1 ± ane.7 (±SD) kg by calendar week 6), waist circumference (− ii.0 ± 3.2 in. by week 6 and − i.5 ± three.ii in. by week 26), body mass alphabetize (− 0.4 ± 0.six kg/one thousand2), and body fat mass (− one.ane ± one.half-dozen kg). This group also had the most pregnant improvement from baseline in quality of life (+ 0.5 ± 0.viii past calendar week 6), body satisfaction (+ 0.2 ± 0.4 past week 6 and week 26), and body appreciation (+ 0.2 ± 0.iii past week 6 and + 0.3 ± 0.3 by week 26). LLLT twice weekly for six weeks could be proposed every bit the optimal frequency and duration for the management of torso weight. Trial registration: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/prove/NCT02877004. Registered August 24, 2016.

Background

Currently in the Usa, about 97 meg adults are overweight, accounting for about 33% of the developed population [1]. Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is a novel non-invasive procedure that lyses excess fat without the negative side effects associated with surgical methods such as liposuction. LLLT has been associated with reductions in waist circumference of 6–12 in. with half-dozen treatments. LLLT has the potential to heighten motivation for weight management treatments by providing immediate positive feedback through reductions in waist circumference recognizable past the individual.

A diverseness of mechanisms of activeness have been proposed to explain how LLLT reduces torso fat [ii]. The two almost popular theories include the lysing of the adipocytes producing transient pores in the cell membrane allowing lipids to flow out [3] and the initiation of lipid peroxidation by LLLT, which temporarily amercement the cellular membrane of the adipocytes by creating pores [4]. Other potential mechanisms are discussed in recent review by Avci et al. [ii]

Clinically, LLLT treatments tin vary from 6 to 28 treatments with a frequency of 1 to 3 times per week depending on the participant's preference and ability to cover the costs of the LLLT and the LLLT device used. In an earlier study, our research team conducted a feasibility study of 45 participants who are overweight or obese evaluating the apply of 12 LLLT treatments over the course of 12 weeks (once per calendar week) with the goal of reducing central adiposity [five]. The LLLT device used 532-nm greenish diodes. LLLT was compared with lorcaserin lonely or in combination with LLLT. Participants were randomized to i of three conditions: LLLT, lorcaserin, and LLLT + lorcaserin. Although the sample size was also small for any statistically meaning findings, the LLLT was observed to be associated with a reduction in body circumference (two.3–iv.0 cm reduction) and a reduction in weight (ane–3.5 kg reduction) with no identified significant adverse events. Some other earlier study past Jackson et al., which used the aforementioned LLLT device (532-nm green diodes) on 68 subjects and randomized them to LLLT or sham treatment iii times a week for 2 weeks, showed that the LLLT subjects had a greater decrease in trunk weight (p < 0.0005) and BMI (p < 0.001) [half-dozen].

Other research has been undertaken an before LLLT device (635-nm red diodes instead of 532-nm green diodes). In the same year, McRae et al. corroborated these findings with 86 patients retrospectively treated with LLT for over 2 weeks. Each patient received 6 treatments evenly spaced over 2 weeks (20 min in front and 20 min in back). In this report, they found a hateful reduction of 1.24 lb (p < 0.0001) [7]. A twelvemonth prior, Jackson had conducted a study of 689 subjects using LLLT 3 times a calendar week for ii weeks (six treatments) and reported significant reduction in circumference of waist, hips, and thighs on average by 5.17 in. between baseline and postal service treatment (p < 0.0001) [8]. These significant reductions in circumference were also noted past Nestor et al. in 80 patients in the same year over six treatments, only no change in BMI was observed [nine].

Uncertainty remains regarding the ideal frequency of LLLT treatments needed for a significant weight loss and torso circumference reduction. The purpose of this current study was to obtain preliminary results regarding the almost efficacious frequency of LLLT treatments to produce body circumference reduction and weight loss.

Methods

Study overview

The nowadays written report was an open-label clinical trial in which participants received 12 LLLT treatments. To keep the number of treatments consistent across written report arms, report participants were randomized to 1 of three treatment frequencies: (1) three times a week for four weeks (group A); (2) twice a calendar week for vi weeks (group B); (iii) once a week for 12 weeks (group C). This written report was approved by the Mayo Dispensary Institutional Review Lath and written informed consent was obtained for all study participants.

Setting

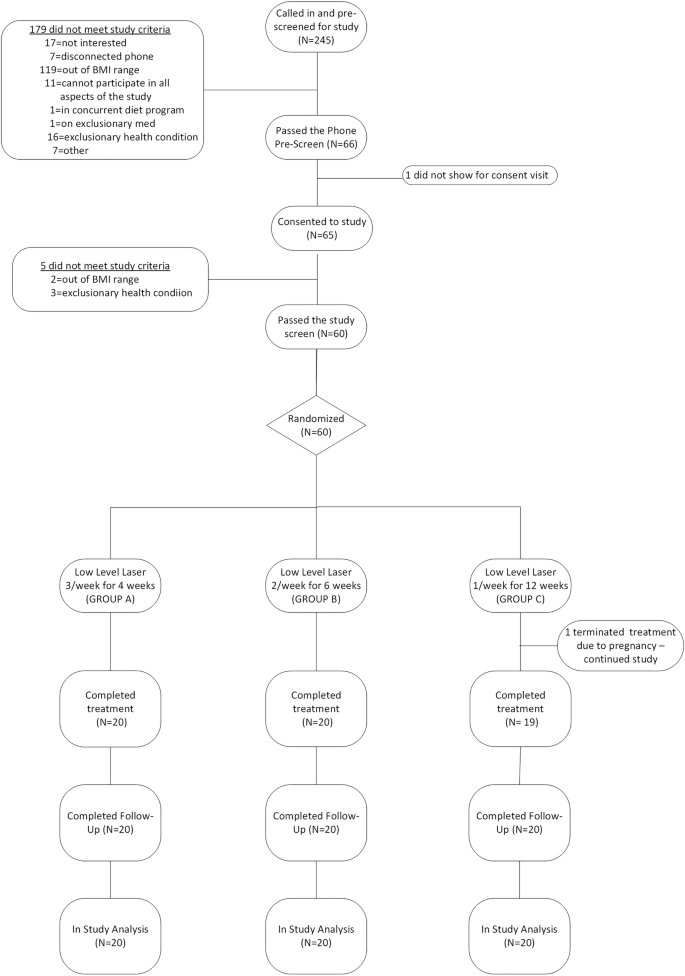

Potential participants were recruited from the local community of Rochester, MN, between September 2016 and Baronial 2017. This study is based on all participants who consented to study, passed written report criteria, and went on to be treated in report. All written report visits and treatments took identify in Mayo Dispensary—Rochester Campus. The study adheres to the espoused guidelines on reporting clinical trials [ten] as demonstrated in the consort diagram presented in Fig. 1.

participant flow in report from offset written report contact to concluding study contact

Participants

Eligible subject area had to have a BMI betwixt 25.0 and 29.ix kg/gii and be motivated to lose weight. All interested individuals called a primal number and underwent a ten-min phone pre-screen. If they passed the phone pre-screen, they were invited to nourish an in-person consent visit. They were excluded if they did not come across report entry criteria which included criteria such as being under the age of 18, not meeting BMI criteria of 25–29.9 kg/m2, not consenting to study, being on a concurrent weight loss program (including weight-loss medicines or do programs), having a weight fluctuation of 20 lb or more than in by half dozen months, having a medical unstable condition, having a positive pregnancy test, having an infection or having had surgery or other external trauma in the area to be treated by the light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation, having a condition that affects weight levels, having a meaning psychiatric condition such as depression (as measured by the CESD-R), existence photosensitive, or having any other condition which may hinder participation or adherence to study procedures.

After participants consented to participation, they signed a written informed consent and were screened for study eligibility. If they passed the post-consent screening procedures, they were invited to participate. If they accepted the invitation, they were assigned the side by side available subject ID number and allocated to the appropriate treatment group using the pre-prepared randomization envelopes. Participants attended their in-person study visits every week at approximately the same time (± 2 h) and aforementioned day of the week.

Randomization

A estimator-generated randomization schedule was prepared by the study statistician using blocks of size North = 6 to ensure that subsequently every sixth participant was randomized and an equal number of subjects was assigned to each handling group. Using this randomization schedule, sealed randomization envelopes were prepared by administrative staff within the Sectionalisation of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics. These randomization envelopes were labeled according to field of study ID number and contained an alphabetize card indicating the treatment assignment for the given field of study.

Interventions

LLLT—The LLLT device consists of a multiple-head depression-level diode laser with six independent diode laser heads. Each diode emits 532 nm (green) light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation lite. In the active device (Erchonia1 LipoLaser; Erchonia Medical, Inc., McKinney, TX) [11], each diode generates a 17-mW output. The average number of treatments tin vary, depending on the adipose makeup on the patient [12]. In this trial, subjects underwent 12 treatments of LLLT at varying frequencies (i, 2, or 3 times per week). The light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation used in this report was an Erchonia® Zerona™ v2.0 Laser. This LLLT has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a non-invasive dermatological esthetic handling to reduce the circumference of hips, waist, and thighs. Lasers were targeted at central adiposity in the belly region for 30 min and the fundamental region of their dorsum for another 30 min. The lasers were placed approximately 6 in. from the targeted expanse during the treatment cycle and each treatment occurred inside 48 h to vii days apart.

The Erchonia® Zerona™ 2.0 Laser (used in this study) has been approved by the FDA (K123237) as a non-invasive dermatological esthetic treatment which can exist used by individuals intending to reduce circumference of hips, waist, and thighs. Justification for the assertion of predictable safety and effectiveness of the Erchonia® Zerona half dozen Headed Scanner (EZ6) for application to reducing body circumference is found through several FDA clearances for Erchonia® Low Level Light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation devices for body circumference reduction indications. For all of the 510(k) clearances, the assigned Product Code is OLI, divers as follows:

-

Device: fatty-reducing low-level laser

-

Regulation description: low-level laser system for esthetic use

-

Definition: non-invasive reduction in fatty layer for trunk contouring

-

Technical method: utilize of low-level laser energy to create pores in adipocyte cells to release lipids (triglycerides)

-

Target surface area: adipocyte cells within the subcutaneous fat layer of the body; this could include abdomen (waist), thighs, and hips

Nether 21 CFR 878,5400, the FDA identifies this generic type of device every bit: "A Low Level Light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation System for Aesthetic Employ is a device using depression level light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation free energy for the disruption of adipocyte cells within the fatty layer for the release of fat and lipids from these cells for non-invasive aesthetic apply."

The procedure administration protocol for each session was as follows:

-

The study participant is correctly fitted with the safe glasses.

-

The participant lies comfortably flat on his or her back on the procedure table such that the front area of the field of study's body is facing upwards.

-

The Erchonia® Zerona 6 Headed Scanner (EZ6) diodes are positioned at a distance of 6 in. higher up the subject'south lower and upper abdomen, stomach, centered along the body's midline (the "line" that vertically "dissects" the trunk into two equal halves).

-

The Erchonia® Zerona 6 Headed Scanner (EZ6) is then activated for xxx min over the discipline's anterior (frontal) region. Each scanner emits to the subject a laser axle of approximately 17 mW with a wavelength of 532 nm, and creates a spiraling circle pattern that is totally random and independent from the others. These patterns overlap each other to guarantee total coverage inside the target expanse of approximately fourscore in.2/516 cm2.

-

The participant and then turns over to lie flat on his or her stomach such that the posterior treatment surface area of the field of study'southward body encompassing the region spanning from the participant's dorsum down though the key trunk region is facing upwards.

-

The Erchonia® Zerona 6 Headed Scanner (EZ6) diodes are positioned at a distance of 6 in. higher up the posterior treatment area, centered along the body's midline, the same as for the inductive region.

-

The Erchonia® Zerona 6 Headed Scanner (EZ6) is then activated for thirty min over the subject'due south posterior region. Each scanner emits to the discipline a laser beam of approximately 17 mW with a wavelength of 532 nm over 15 min, and creates a spiraling circumvolve pattern that is totally random and independent from the others. These patterns overlap each other to guarantee total coverage inside the target area of approximately fourscore in.two/516 cmii. This converts to each patient receiving approximately 59.ii MJ/cm2 in energy density in the front and the same amount in the back, per session.

-

The participant'due south prophylactic glasses are removed and the procedure administration session is over.

An Erchonia practiced trained the study staff in-person on the use and maintenance of the LLLT on December 12, 2013 for a prior report utilizing LLLT. This training session has been documented. They were bachelor for on-the-spot questions and for whatsoever online retraining, every bit needed. The report coordinators were under the direction of the nurse coordinator/supervisor (DFR).

Behavioral intervention—Upon study entry, the study coordinator completed a brief (10-min) individual behavioral intervention introducing and reviewing a patient education resource, the Mayo Clinic "My Weight Solution©" manual, with the study participant, and a copy was given to them to keep. Topics in this manual included motivational strategies, social back up, goal-setting strategies, nutritional recommendations, and strategies for physical activity.

Outcomes and rubber measures

The chief outcomes included (ane) 3% body weight loss from baseline; (2) anthropometric measures of waist (WC) and hip circumference; (3) body composition measurements via InBody 770, a bioelectrical impedance (BIA) scale used to mensurate participant weight, pinnacle, and body composition assay (intracellular h2o, extracellular water, dry lean mass, body fat mass), and gauge visceral fat [13]; (4) linear analogue self-assessment (LASA) to self-assess quality of life (QoL) [xiv,15,16]; (5) participant motivation to reduce weight, self-assessed at baseline prior to study interventions; (6) Body Areas Satisfaction Scale (BASS), a subscale from the Multidimensional Trunk-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ) [17] used to self-assess participants' self-perceived torso image and satisfaction of eight specific torso areas [18, 19]; (7) Torso Appreciation Scale (BAS), a scale to self-assess positive body image [twenty]; and (8) adherence to the study interventions recorded by staff every bit attendance to the laser treatments.

The safety measures included (i) adverse events, (2) concomitant medication, (3) self-reported depression using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Calibration Revised (CESD-R), and (4) urine pregnancy tests.

Study schedule

Report visits were divided into 3 phases: screening (09/xxx/xvi to 08/27/17), treatment (x/04/16 to xi/thirty/17), and post-treatment (11/11/16 to 03/05/xviii). All participants were in report for 6 months. The screen phase included a pre-screen phone interview and a combined consent/screen/randomization visit. Once randomized, participants entered the handling phase based on their randomization schedule. If randomized to group A—the participant reported for treatment for 4 sequential weeks (three times per week); if randomized to grouping B—the participant reported for treatment for 6 sequential weeks (2 times per week); if randomized to group C—the participant reported for treatment for 12 sequential weeks (ane fourth dimension per week). One week after the last treatment, participants received a safety phone contact. Participants were required to complete an in-person written report visits at weeks 4, 6, 12, and 26 during which fourth dimension the written report staff collected data pertaining to QoL (LASA), torso image (BAS and BASS), prophylactic (agin events and concomitant medication), every bit well as vitals, BIA, and trunk measurements. In addition, during the final visit (week 26), satisfaction was measured via an terminate-of-written report self-assessment survey.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint for this investigation was change in WC from baseline, and for this endpoint a reduction of 1.0 cm was considered clinically meaningful. Based on preliminary data from our previous study [5], we determined that for this randomized phase II study, a sample size of N = 20 per group would provide statistical power (one-tailed, alpha = 0.20) of approximately 80% to assess whether boosted studies are warranted [21].

Data were summarized using hateful ± SD for continuous variables and frequency percentages for nominal variables. Anthropometric measures at each of the study visits (weeks 4, vi, 12, and 26) were compared to baseline using the paired t test and compared across treatment groups using analysis of covariance with the baseline value included equally the covariate. Three pairwise treatment group comparisons were of specific involvement: the change in WC from baseline to week 4 was compared between those receiving LLLT three per calendar week and those receiving LLLT twice and once per week; and the alter in WC from baseline to week 6 was compared betwixt those receiving LLLT twice per week and those receiving LLLT once per calendar week. The results of these comparisons are summarized by presenting the effect estimate forth with ninety% confidence intervals and one-tailed p values. All other measures were analyzed using two-tailed tests. If the overall comparing across handling groups was statistically meaning at the p < 0.05 level, linear contrasts were used to perform pairwise treatment grouping comparisons. Information were managed using the REDCap tool hosted at Mayo Clinic [22], and analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software [23].

Results

Report recruitment included internet postings (75%), wait lists (14%), word of rima oris (viii%), and internal flyers (iii%). Of the 245 participants pre-screened, lx were consented and randomized (20 per grouping) (Fig. 1). All participants simply one (98%) completed at least 10 of the 12 treatments. For group A, xviii (ninety%) participants completed all 12 sessions and 2 (10%) completed eleven sessions. For group B, 17 (85%) participants completed all 12 sessions, 2 (10%) completed 11 sessions, and 1 (v%) completed ten sessions. For group C, xviii (90%) participants completed all 12 sessions, 1 (5%) completed 11 sessions, and 1 (five%) completed 7 sessions (this last participant had to end the treatments early due to pregnancy; see details beneath).

The majority of participants were white (95%), female person (90%), married/living as married (72%), with at least a iv-year college degree (53%), boilerplate age of 43.vii years (± 9.2), and moderately active (72%). No between-group differences in concern, motivation, importance, and conviction in weight loss, as well as stress level were detected using visual analogue scales (0 to x, with 0 being the lowest and x being the highest) (come across Table 1).

Body anthropometric and limerick measurements are summarized in Table 2, and the percentage of participants who had weight loss of ≥ iii% is summarized in Table three. In those receiving LLLT iii times per week for iv weeks (grouping A), there were no significant reductions from baseline in weight, BMI, or waist circumference at whatsoever time indicate. In those receiving LLLT 2 times per week for vi weeks (group B), weight, BMI, and waist circumference were all significantly reduced from baseline at weeks four and half-dozen, with meaning reductions in waist circumference also observed at 12 and 26 weeks. For those receiving LLLT in one case per calendar week for 12 weeks (group C), waist circumference was plant to be significantly reduced from baseline at calendar week vi. For grouping A, no significant changes in body composition measurements from baseline were detected at any fourth dimension periods. For groups B and C, significant reductions from baseline were observed starting at calendar week 4 for trunk fat mass, percent body fatty, and visceral fat. When changes from baseline were compared across groups, the only significant finding was for the change in torso fat mass at calendar week 6, with group B experiencing a larger reduction compared to grouping A.

In order to assess whether an increased frequency of LLLT was associated with a larger reduction in body circumference, 1-tailed tests were used for 3 comparisons of specific interest including the change in WC from baseline to week 4 for group A compared to group B and grouping A compared to grouping C as well equally the change in WC from baseline to week six for group B versus grouping C. In all cases, no meaningful differences were plant (calendar week 4—A vs. B effect estimate = + 0.62, 90% CI − 0.68 to + ane.92, one-tailed p = 0.783; week 4—A vs. C effect estimate = − 0.50, 90% CI − one.80 to + 0.lxxx, one-tailed p = 0.266; week 6—B vs. C effect approximate = − 0.40, 90% CI − 1.98 to + ane.18, 1-tailed p = 0.340). When all other measurements were compared across groups, reductions in weight and BMI at six weeks were found to be statistically meaning with those in group B having significantly larger reductions compared to group A (Tabular array iii).

No significant differences were observed beyond groups with respect to changes from baseline in motivation, body satisfaction, body appreciation and overall quality of life (QoL) (Table 4), except for the QoL domain of physical, which was meaning at week 12 for group B. However, changes across time show a positive trend in BASS (weeks six, 12, and 26), BAS (weeks half-dozen, 12, and 26), motivation to lose weight, overall QoL (weeks half dozen and 12), and physical QoL (weeks half dozen, 12, and 26) in group B compared to baseline.

One serious adverse event of pregnancy was reported later on the 7th treatment in a participant in group C. All treatments were stopped and the patient was followed through a healthy delivery. During the course of the 26-calendar week written report, 29 (48%) of the participants reported 39 adverse events, none of which were determined to be related to the LLLT. Depression was monitored throughout the report using the CESD-R with three participants reporting situational low at some point during the study. Upon further assessment, the situational depression was constitute not to be related to the written report and the patient was cared for in the appropriate way per advisable medical care. These participants continued in the study and treatment was non halted.

At the end of our study, participants were asked questions near changes made in lifestyle (due east.g., reducing calorie intake, making healthier nutrition choices, exercising, increasing water intake, wearing body-constricting undergarments) during the 26-week study period. The percent of patients reporting lifestyle changes was similar across groups with 50%, 45%, and sixty% reporting 1 or more than lifestyle changes in groups A, B, and C, respectively. In addition, no significant difference was observed betwixt groups with respect to satisfaction with treatment assignment (overall satisfaction with the frequency of LLLT was reported as "satisfied" or "extremely satisfied" at week 26 (end of study) by fifty% (10/20) in group A, 65% (xiii/20) in grouping B, and forty% (8/20) in group C) (Table 5).

Discussion

In this pilot project, iii frequencies of LLLT handling therapy were examined and results indicate that treating adults twice weekly for 6 weeks (group B) was the best choice for adults who are overweight and motivated to lose weight compared to one time a week (group C) or 3 times a week (grouping A).

For grouping B (2 LLLTs per week for 6 weeks), a meaning reduction was noted when compared to grouping A (3 LLLTs per week for 4 weeks) in weight and BMI; within groups, a significant reduction from baseline was noted in group B for weight, BMI, body fat mass, and percent body fat at weeks 4 and 6, besides equally a reduction in visceral fat level at weeks 4, 6, and 12; a reduction was noted in waist circumference at weeks iv, 6, 12, and 26; a meaning waist-to-hip ratio reduction was noted at week 12; improvement in body area satisfaction and body appreciation was noted at weeks 6, 12, and 26 and comeback in overall quality of life at weeks half dozen and 12. No side furnishings were reported related to LLLT in whatever of the three handling weather condition. Overall satisfaction was college among participants assigned to twice-weekly treatments (group B) than the other groups. For group B, 25% of the patients achieved 3% weight loss at end of the treatments (week six) and 15% continued to maintain the 3% weight loss from baseline at finish of study (week 26).

The finding that participants receiving two LLLTs per calendar week for half dozen weeks (grouping B) experienced greater reduction in weight and body fatty mass at half-dozen weeks compared to those receiving 3 LLLTs per calendar week for 4 weeks (group A) suggests that a longer duration of moderate intensity is preferable when compared to a short duration of higher-intensity therapy. In addition, no evidence was observed to suggest that 12-calendar week outcomes were improved with 12 weeks of in one case-weekly LLLT (grouping C) compared to 6 weeks of twice-weekly LLLT (group B). Observed differences at 12 weeks suggest that the moderate intensity (2 LLLTs per calendar week for half-dozen weeks—group B) is preferred.

Consistent with previous literature, LLLT was associated with reduction in weight, BMI, WC, waist-to-hip ratio, and body fat mass. Participants in this pilot project demonstrated that these effects may be ideally achieved when they are delivered twice weekly. This association is confirmed by some other report of 67 participants who were overweight and were randomized to 6 LLLT treatments of either true LLLT or sham LLLT [six]. Within this placebo-controlled written report, 63% of the active participants (vs. 6% in the sham arm) lost a combined total of ≥ 3.0 in. from waist, hip, and bilateral thighs from baseline to end of treatment. In our study, we observed a loss of two.iv in. in waist circumference at end of handling (compared to baseline) and a reduction of 1.5 in. at stop of study compared to baseline. It is important to annotation that retrospective studies accept supported the trunk measurement reductions achieved (e.grand., waist, hips, thighs) with LLLT and reported concomitant decreases in weight [vii].

The current Us guidelines for clinical weight management recommend a vi-month weight loss goal of 3–5% from baseline weight [24]. Even such a modest weight loss tin produce wellness benefits through reductions in triglycerides, blood sugars, and take chances for diabetes, with larger weight loss producing greater benefits. In this written report, all groups were able attain this, but group B had the most consistent weight loss throughout the written report. We advise that LLLT 2 times per week for 6 weeks achieves an appropriate balance between intensity and duration with the LLLT protocol. We were not able to detect whatsoever prior published studies focused on these weight loss goals for patients who were overweight with a BMI of 25–29.9 kg/m2. Past studies have focused on patients who are obese and have used medications (i.eastward., orlistat, metformin, naltrexone/bupropion, lorcaserin) or surgical interventions with other lifestyle modifications (i.due east., behavioral interventions). In these studies, a 5% weight loss from baseline has been achieved in 33% to 80% [5, 24,25,26,27] of participants, only whether such a loss has been able to be maintained long term is unknown.

Depression QoL has been associated with obesity and overweight [28, 29]. Indeed, one by written report compared QOL of individuals who were overweight and obese to the general population and observed them to have lower QOL, especially in the concrete and mental domains. With weight loss, these QoL domains improved [28]. Other studies have observed that QoL domains most improved with weight loss are the concrete and mental domains [28, 30,31,32,33,34]. In the present study, we observed that LLLT in group B was associated with improvements in overall QoL. Specifically, nosotros observed significant improvement in the concrete role domain of QOL at weeks 6, 12, and 26 (+ 0.viii ± 1.1, + 1.0 ± 1.i, and + 0.vii ± 1.1, respectively). We observed that participants had an improved mental attitude toward their body (better appreciation and satisfaction) as well as improved motivation after starting LLLT. These changes were insignificant for group B in which the tendency continued until the finish of the study.

Across the three groups, 55–65% of the participants reported that LLLT was helpful and 35–60% said they would recommend it to friends. Participants may have set up unrealistic expectations of a larger weight loss with LLLT treatment and became disappointed when those expectations were not met. This mind prepare phenomenon is not unusual in weight loss programs where setting unrealistic expectations is a barrier to weight loss [35]. In a study of 60 females who are obese (hateful BMI of 36.3 kg/mii) in which participants ready a goal of 32% trunk weight reduction, and the boilerplate weight loss was less than 17% from their baseline weight, participants accounted the program a failure [36]. Two other studies with individuals with BMIs ≥ 40 kg/m2 or higher observed this same phenomenon [37, 38]. Individuals with higher baseline weight may have more unrealistic goals for weight loss and loftier unrealistic expectations ready prior to the program which led to poor programme compliance and worse outcomes [35]. In the current investigation, study staff provided authentic information apropos LLLT and salubrious weight loss expectations (5–ten% per US guidelines [24]). This discussion may have improved adherence and reduced report attrition. In a prior study of 1785 patients who were obese throughout 23 Italian medical centers, higher weight loss expectations were associated with higher 12-month attrition [39]. In add-on, a recent review of xix weight loss studies observed that higher stages of change at baseline, higher initial weight loss, higher education, and older age are predictors of adherence to weight loss interventions [40]. Future studies should include counseling components to manage expectations of weight loss.

Finally, all but one prior LLLT studies take focused their outcome measures of weight, BMI, and anthropometric measurements at end of treatment and not on long-term (half dozen months) outcomes. We have evaluated outcomes 3 months later on LLLT therapy completion [5]. In that report, we observed that patients receiving LLLT had no weight changes (− ane.iv ± 3.vi kg) and waist circumference lost centimeters (− 2.8 ± 4.three cm) within 3 months of the last laser treatment [5]. In the current report, we observed that equally motivation decreased mail service-treatment, the success fabricated toward weight loss and reduced waist circumference macerated and weight and inches were regained. In club for weight loss maintenance to be successful, information technology should be maintained for 2 to 4 years [41] and, to date, the just successful programs take been ones which consist of loftier physical activity, depression-calorie/depression-fat diets, and daily self-monitoring [24, 41, 42]. This can just be accomplished through motivational enhancement. More than studies are needed to determine the long-term maintenance efficacy of LLLT.

Although our small sample size is acceptable for a pilot study, it limits the ability to detect significant differences between groups. In add-on, the open up-label design limits our study due to patient selection bias [43], participant retentivity bias [44], and participant operation bias [45]. Some eligible participants decided non to participate knowing at that place was a chance they would not receive their preferred schedule. Since LLLT is a new weight loss intervention, it is not known what healthy lifestyle recommendations can exist tailored to LLLT, such as more than focus on strength training or nutritional guidelines. Nosotros provided all participants with a cocky-assistance guide on weight loss at study enrollment and a brief orientation to the manual. We did not provide any further reference to the manual during study participation or whatever counseling thereafter. 50-5 pct of the participants indicated the counseling manual was helpful only would accept welcomed behavioral intervention throughout the study. A strengthened behavioral modification component could exist explored as a potential co-intervention to LLLT for futurity studies.

Conclusions

Providing 12 LLLT treatments over the course of 6 weeks twice per week is effective for reducing body weight, BMI, body fatty mass, and percent body fat too as improving body satisfaction, trunk appreciation, and overall quality of life. At end of treatment, 30% of participants who were overweight (BMI of 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2) in the twice-weekly grouping lost greater than three% of baseline weight. More research should exist conducted to determine if boosted improvements in body anthropometric measurements can be achieved by calculation other non-burdensome components to the LLLT intervention such equally behavioral counseling.

Availability of data and materials

All data supporting the study findings are contained within this manuscript and within file NCT02877004 on www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

Abbreviations

- BIA:

-

bioelectrical impedance

- BAS:

-

Body Appreciation Calibration

- BASS:

-

Trunk Areas Satisfaction Scale

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CESD-R:

-

Center for Epidemiology Studies Low Scale—Revised

- LASA:

-

Linear Analogue Self-Assessment

- LLLT:

-

low-level light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation therapy

- MBSRQ:

-

Multidimensional Body-Cocky Relations Questionnaire

- QoL:

-

quality of life

- WC:

-

waist circumference

References

-

Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity amid adults: U.s.a., trends 1960–1962 through 2007–2008 [http://world wide web.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/hestat/obesity_adult_07_08/obesity_adult_07_08.pdf] Accessed 01 Nov 2011

-

Avci P, Nyame TT, Gupta GK, Sadasivam 1000, Hamblin MR (2013) Depression-level laser therapy for fat layer reduction: a comprehensive review. Lasers Surg Med 45(6):349–357

-

Neira R, Arroyave J, Ramirez H, Ortiz CL, Solarte E, Sequeda F, Gutierrez MI (2002) Fatty liquefaction: event of low-level light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation energy on adipose tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg 110(three):912–922 discussion 923-915

-

Chen AC, Arany PR, Huang YY, Tomkinson EM, Sharma SK, Kharkwal GB, Saleem T, Mooney D, Yull Iron, Blackwell TS et al (2011) Low-level laser therapy activates NF-kB via generation of reactive oxygen species in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. PLoS I 6(7):e22453

-

Croghan It, Ebbert JO, Schroeder DR, Hurt RT, Hagstrom V, Clark MM (2016) A randomized, open-label pilot of the combination of depression-level laser therapy and lorcaserin for weight loss. BMC Obes 3:42

-

Jackson RF, Roche GC, Shanks SC (2013) A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial evaluating the ability of depression-level light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation therapy to improve the appearance of cellulite. Lasers Surg Med 45(3):141–147

-

McRae E, Boris J (2013) Contained evaluation of low-level laser therapy at 635 nm for non-invasive body contouring of the waist, hips, and thighs. Lasers Surg Med 45(one):1–seven

-

Jackson RF, Stern FA, Neira R, Ortiz-Neira CL, Maloney J (2012) Application of depression-level laser therapy for noninvasive body contouring. Lasers Surg Med 44(iii):211–217

-

Nestor MS, Zarraga MB, Park H (2012) Effect of 635nm low-level laser therapy on upper arm circumference reduction: a double-bullheaded, randomized, sham-controlled trial. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 5(2):42–48

-

Consort: Transparent Reporting of Trials [www.consort-statement.org/consort-statement/menses-diagram] Accessed 15 Aug 2016

-

Zerona [http://www.myzerona.com/professional person] Accessed 01 Sept 2011

-

Mulholland RS, Paul Doc, Chalfoun C (2011) Noninvasive body contouring with radiofrequency, ultrasound, cryolipolysis, and depression-level light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation therapy. Clin Plast Surg 38(3):503–520 vii-3

-

InBody 770: Premium Solution for Your Wellness [http://www.e-inbody.com/global/product/InBody770.aspx] Accessed 15 March 2016

-

Singh JA, Satele D, Pattabasavaiah S, Buckner JC, Sloan JA (2014) Normative information and clinically significant consequence sizes for single-item numerical linear analogue self-assessment (LASA) scales. Wellness Qual Life Outcomes 12(one):187

-

Hyland M, Sodergren Southward (1996) Development of a new blazon of global quality of life calibration, and comparing of performance and preference for 12 global scales. Qual Life Res five(five):469–480

-

Locke DE, Decker PA, Sloan JA, Brown PD, Malec JF, Clark MM, Rummans TA, Ballman KV, Schaefer PL, Buckner JC (2007) Validation of single-item linear analog calibration assessment of quality of life in neuro-oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 34(6):628–638

-

Cash TF (2015) Multidimensional trunk–self relations questionnaire (MBSRQ). In: Wade T (ed) Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders. Springer, Singapore

-

Cash T (1994) The multidimensional torso-self relations questionnaire user'south transmission. Norfolk

-

Clark MM, Croghan It, Reading S, Schroeder DR, Stoner SM, Patten CA, Vickers KS (2005) The relationship of body image dissatisfaction to cigarette smoking in college students. Body Paradigm two(3):263–270

-

Avalos L, Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow North (2005) The body appreciation calibration: development and psychometric evaluation. Torso Prototype two(3):285–297

-

Rubinstein LV, Korn EL, Freidlin B, Hunsberger S, Ivy SP, Smith MA (2005) Design issues of randomized phase Two trials and a proposal for phase II screening trials. J Clin Oncol 23(28):7199–7206

-

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research computer science support. J Biomed Inform 42(2):377–381

-

SAS Institute Inc (2017) SAS/STAT User's Guide—Version 9.4. SAS Found, Cary, NC

-

Jensen K, Ryan D, Apovian C, Ard J, Comuzzie A, Donato M, Hu F, Hubbard V, Jakicic J, Kushner R et al (2014) 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the direction of overweight and obesity in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 63(25 Role B):2985–3023

-

Ornellas T, Chavez B (2011) Naltrexone SR/bupropion SR (Contrave): a new approach to weight loss in obese adults. P&T 36(5):255–262

-

Fidler MC, Sanchez M, Raether B, Weissman NJ, Smith SR, Shanahan WR, Anderson CM (2011) A one-year randomized trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in obese and overweight adults: the Bloom trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(10):3067–3077

-

O'Neil PM, Smith SR, Weissman NJ, Fidler MC, Sanchez M, Zhang J, Raether B, Anderson CM, Shanahan WR (2012) Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in type two diabetes mellitus: the BLOOM-DM study. Obesity twenty(7):1426–1436

-

Blissmer B, Riebe D, Dye G, Ruggiero L, Greene K, Caldwell M (2006) Health-related quality of life following a clinical weight loss intervention amongst overweight and obese adults: intervention and 24 month follow-up furnishings. Health Qual Life Outcomes iv:43

-

Hajian-Tilaki G, Heidari B, Hajian-Tilaki A (2016) Lonely and combined negative influences of diabetes, obesity and hypertension on health-related quality of life of elderly individuals: A population-based cross-sectional report. Diabetes Metab Syndr 10(2 Suppl ane):S37-42.

-

Batsis JA, Clark MM, Grothe K, Lopez-Jimenez F, Collazo-Clavell ML, Somers VK, Sarr MG (2009) Self-efficacy after bariatric surgery for obesity. A population-based cohort study. Appetite 52(3):637–645

-

Batsis JA, Lopez-Jimenez F, Collazo-Clavell ML, Clark MM, Somers VK, Sarr MG (2009) Quality of life after bariatric surgery: a population-based cohort study. Am J Med 122(11):1055 e1051–1055 e1010

-

Rothberg AE, McEwen LN, Kraftson AT, Neshewat GM, Fowler CE, Burant CF, Herman WH (2014) The impact of weight loss on health-related quality-of-life: implications for price-effectiveness analyses. Qual Life Res 23(iv):1371–1376

-

Pan A, Kawachi I, Luo N, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB, Okereke OI (2014) Changes in torso weight and health-related quality of life: two cohorts of US women. Am J Epidemiol 180(3):254–262

-

Leon-Munoz LM, Guallar-Castillon P, Banegas JR, Gutierrez-Fisac JL, Lopez-Garcia E, Jimenez FJ, Rodriguez-Artalejo F (2005) Changes in body weight and health-related quality-of-life in the older adult population. Int J Obes 29(11):1385–1391

-

Lagerros YT, Rossner S (2013) Obesity direction: what brings success? Ther Adv Gastroenterol half dozen(one):77–88

-

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G (1997) What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients' expectations and evaluations of obesity handling outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol 65(1):79–85

-

Linne Y, Hemmingsson E, Adolfsson B, Ramsten J, Rossner South (2002) Patient expectations of obesity treatment—the experience from a day-intendance unit of measurement. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 26(5):739–741

-

Foster GD, Wadden TA, Phelan S, Sarwer DB, Sanderson RS (2001) Obese patients' perceptions of handling outcomes and the factors that influence them. Arch Intern Med 161(17):2133–2139

-

Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Molinari East, Petroni ML, Bondi M, Compare A, Marchesini One thousand, Group QS (2005) Weight loss expectations in obese patients and handling attrition: an observational multicenter study. Obes Res thirteen(eleven):1961–1969

-

Leung AWY, Chan RSM, Sea MMM, Woo J (2017) An overview of factors associated with adherence to lifestyle modification programs for weight management in adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(8):922.

-

Wing RR, Hill JO (2001) Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr 21:323–341

-

The Practical Guide: Identification, Evaluation, and Handling of Overweight and Ovesity in Adults [www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/prctgd_c.pdf] Accessed 05 Feb 2019

-

Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M (2001) Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 323(7303):42–46

-

Halpern SD (2003) Evaluating preference effects in partially unblinded, randomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol 56(2):109–115

-

Rucker G (1989) A two-stage trial pattern for testing treatment, cocky-choice and handling preference effects. Stat Med eight(4):477–485

Acknowledgments

Special thank you to the infrequent research staff of the Mayo Dispensary Department of Medicine Clinical Research Office for their patience and persistence in helping to collect, compile, and organize these data. Special thank you to Bonnie Donelan Dunlap, Donna Rasmussen, and Sara Gifford for all their hard piece of work and dedication to this study. The authors as well wish to thank the report participants who participated in this clinical trial, without whom this project would not have been possible.

Funding

The data entry system used was REDCap, supported in part by the Center for Clinical and Translational Science laurels (UL1 TR000135) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). This funding body had no oversight and did not provide any input or management to the current written report design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, too as this report.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors participated in the written report concept and blueprint, assay and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the paper, and accept seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

I.T.C.—conceived of the study concept and design; obtained funding and provided administrative, technical, and material support; had full oversight of the written report conduct during information drove; had total access to all the data in the report and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accurateness of the data analysis; and also drafted the manuscript and participated in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

J.O.Eastward., R.T.H., G.D.J.—participated in the study pattern and were responsible for condom screening for written report entry and the safety oversight of the written report subjects while on study. They as well participated in the review and estimation of study results, and critical revision of the manuscript for of import intellectual content.

S.C.F.—reviewed the study menstruum, screened the study participants, oversaw all the study visits and LLLT treatments, also every bit worked with the study clinicians and PI to address patient safe issues and with the PI and statistician to clean out the electronic data as well every bit provide reviews and edits to the manuscript.

D.R.S.—participated in the report design and was responsible for data quality checks and data analysis; he besides had total admission to all the data in the report and takes full responsibleness for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data assay as well as participating in the manuscript reviews and edits.

Yard.G.C.—participated in the report design and was instrumental in the development of the patient manual "My Weight Solution." He provided training to the staff on the brief intervention utilizing this manual and participated in the manuscript review and provided edits.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics and consent to participate

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, this study was reviewed and approved (ID 16-004817) by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB). Mayo Clinic IRB–approved written informed consent was obtained for all study participants prior to study participation.

Consent to publish

Not applicative.

Competing interests

I.T.C.—no competing interests to declare.

R.T.H.—reports consulting fees from Nestlé, and inquiry funding from NIH and InBody outside the submitted work.

D.R.South.—no competing interests to declare.

Southward.C.F.—no competing interests to declare.

1000.D.J.—no competing interests to declare.

Thousand.M.C.—no competing interests to declare.

J.O.Due east.—no competing interests to declare.

Boosted data

Publisher's notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided yous give advisable credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and bespeak if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Croghan, I.T., Hurt, R.T., Schroeder, D.R. et al. Low-level light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation therapy for weight reduction: a randomized pilot written report. Lasers Med Sci 35, 663–675 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-019-02867-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1007/s10103-019-02867-five

Keywords

- Adiposity

- Overweight

- Weight loss

- Clinical trial

taylorcortall1997.blogspot.com

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10103-019-02867-5

0 Response to "Low-level Laser Therapy for Fat Layer Reduction a Comprehensive Review"

Postar um comentário